“Fast and Furious” or “Slow and Steady”: Which Is Better for Weight Loss?

What should your weight loss approach be: fast and furious or steady and slow? Well, for once, you might wish to take inspiration from the hare.

Many recommend losing weight slowly and gradually.

Supposedly, it’ll boost your chances of keeping the weight off long-term. But here’s the kicker.

It doesn’t.

A 2014 study found that a similar percentage (~76%) of participants assigned to the “slow” and “fast” weight loss groups had regained most of their lost weight at the 3-year mark.

So, why spend more time losing the same weight? That’s right. You shouldn’t. Faster is better.

In this article, learn:

- The definitions of “fast” and “slow” weight loss

- How to side-step the “metabolic slowdown” associated with fast weight loss

- What truly matters for weight loss maintenance

What’s “fast”? What’s “slow”?

- Slow: ≤ 1% of body weight weekly

- Fast: > 1% of body weight weekly

Why is fast weight loss better?

You save time

Starting with the most obvious, time.

If you lose the same amount of weight in 6 months instead of a year, that’s clearly a win.

You stay more motivated

💬 “The slow rate was annoying me, and I’d always stop because I felt like there was no improvement.” — a sentiment commonly seen on Reddit

Results are motivating.

When you take things slow, too slow, you might feel like whatever you’re doing isn’t working, get disenchanted, and prematurely throw in the towel (when all you needed was to stick to it a little longer).

Research agrees.

This 2013 study suggests that the more weight you lose in the first few weeks of a diet, the more:

- Weight you’ll lose in the long run

- Successful you’ll be at keeping it off

Forecast of metabolic adaptation: low

A common argument against fast weight loss is that it causes a more significant metabolic slowdown (i.e., metabolic adaptation) than a slower approach.

It does so by:

1️⃣ Messing up the balance of appetite-regulating hormones: Thyroid hormone, leptin, and insulin go down👇, while ghrelin and cortisol go up👆. The result is more hunger.

2️⃣ Downregulating energy expenditure: Research shows that when you lose ≥ 10% of your body weight, your total TDEE will end up about 10% to 15% below what we’d expect based on body mass changes alone. This lower-than-expected drop stems from a combination of BMR and NEAT.

1️⃣ Basal metabolic rate (BMR): Calories burned at rest; ~70% of TDEE.

2️⃣ Thermic effect of feeding (TEF): Calories burned from eating, digesting, metabolizing, and storing food; ~10% of TDEE.

3️⃣ Exercise activity thermogenesis (EAT): Calories burned during intentional exercise; ~5% of TDEE, but it depends on how much you exercise.

4️⃣ Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): Calories burned for any movement that isn’t intentional exercise; ~15% of TDEE.

So, essentially, the argument is that the faster you try to lose weight, the harder your body pushes back. (It’s like stretching a rubber band.)

In short:

- You become a hyperfocused, food-seeking missile

- Worse, your body’s now burning fewer calories

But! How badly you’ll experience metabolic adaptation has little to do with weight loss speed.

Instead, it comes down to how close you are to your “lower intervention point”. This brings us to:

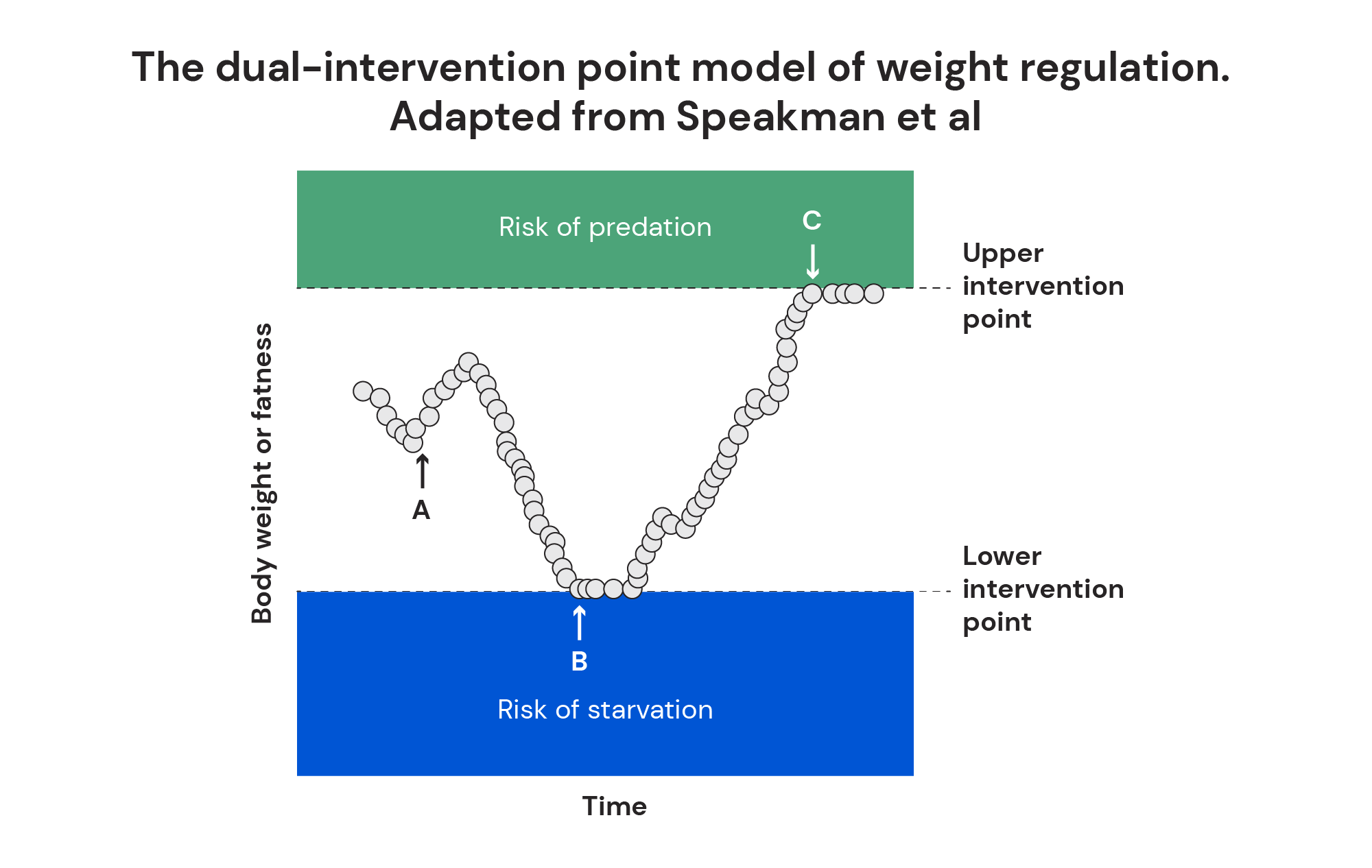

The dual-intervention point model

Remember how we mentioned that your body prefers to keep you at a set body weight range?

This is related to a theory called the “dual intervention point model” of weight regulation.

- Above upper intervention point: Predation risk (back when we were on predators’ menus) increases. Gaining more weight is difficult.

- Below lower intervention point: Starvation risk increases. Losing more weight is difficult (because metabolic adaptation kicks in).

Look at the white space in the picture.

Between those 2 thresholds is a wide range where environmental and behavioral factors dictate your body fat.

Meaning? If you have a lot of weight to lose, you’re likely very, very far away from your lower intervention point. This means your body is unlikely to fight you much as you lose weight — no matter how quickly you do it.

But what if you’re already pretty lean?

If your ideal body weight calls for a body fat percentage close to or even possibly lower than your lower intervention point (e.g., competitive bodybuilding), here’s what you need to know:

Refresher: A drop in BMR and NEAT causes your TDEE to end up about 10% to 15% lower than expected based on body mass changes alone.

Because you have control over your NEAT (unlike BMR), simply staying active as you usually would throughout the day will help keep your TDEE up, mitigating metabolic adaptation.

What about muscle mass loss?

When matching for similar total weight loss, faster rates of weight loss result in a greater proportion of lean body mass (LBM) loss.

Isn’t that bad?

1️⃣ LBM is more metabolically active (i.e., burns more calories) than fat body mass (FBM).

2️⃣ The more LBM you lose, the more the body upregulates appetite.

Yes, but you can minimize LBM loss during fast weight loss. Here are 2 strategies.

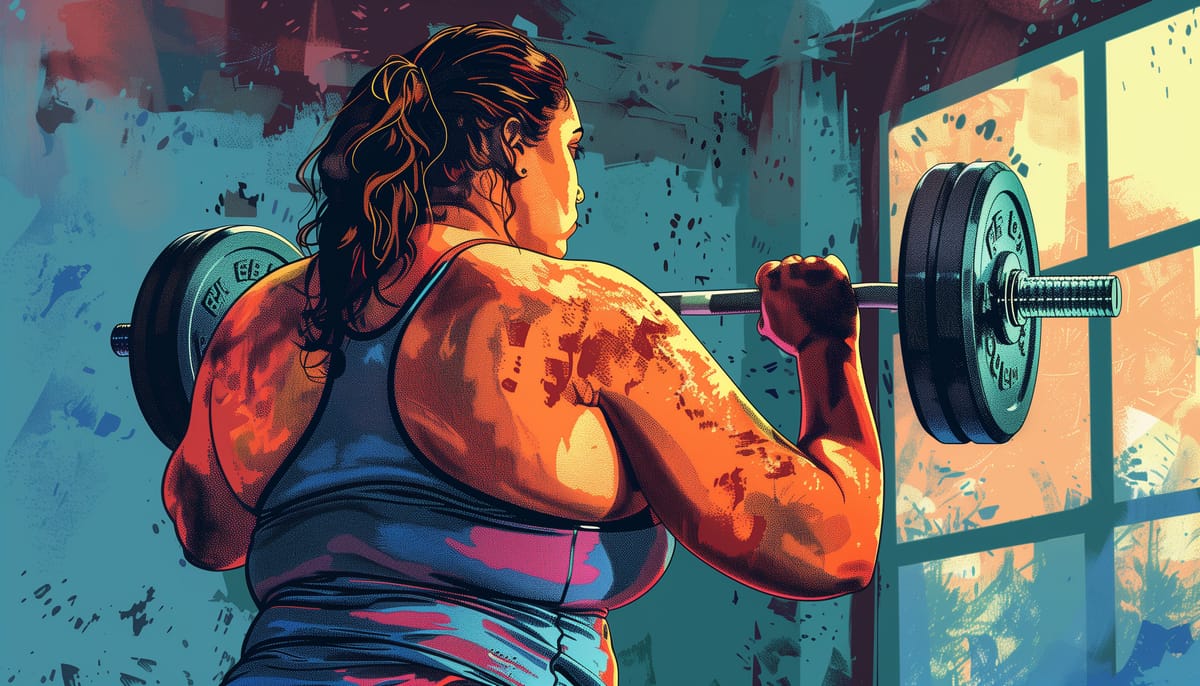

#1: Strength train

Strength training (weight-bearing exercises like weightlifting, yoga, and Pilates) tells your body, “Hey! Don’t touch these muscles. We need them. Burn something else!”

As a result, your body will prioritize losing weight from FM instead of LBM.

This has positive impacts on your metabolic rate and appetite regulation.

#2: Eat a high-protein diet

Protein provides the building blocks — amino acids — your body needs to maintain and potentially build muscle.

The amount of protein you need to eat to preserve as much muscle mass as possible depends on your current weight and lifestyle.

In general, if you’re:

- Overweight or obese: Aim for 1.2 to 1.5 g of protein per kg of body weight

- Within the healthy weight range: Aim for 1.6 to 2.4 g of protein per kg of body weight

Another upside to eating a high-protein diet? It’s incredibly satiating.

This makes it a potent counteracting force to any hunger-driving signals stemming from LBM loss.

Disclaimer

Someone losing weight faster will likely still lose more muscle mass than someone who’s doing so gradually. This is assuming the same body composition, resistance training program, and dietary habits (including daily protein intake).

But for most people who aren’t usually very lean to begin with, this difference won’t be catastrophic.

Besides, the higher loss in muscle mass shouldn’t be a dealbreaker if seeing fast results is the only way to keep you motivated.

It’s possible to lose weight too fast

We’ve established that fast isn’t necessarily bad.

But too fast — a loss of 1.4% to 2% of body weight weekly — can be. That’s because this sets you up for a significant calorie deficit.

🧮 To illustrate, I plugged the following into a calorie calculator:

- Age: 25

- Gender: Female

- Height: 170 cm

- Weight: 65 kg

- Activity: Moderate, exercise 4 to 5 times weekly

It gave me the following calorie estimates for:

- Weight maintenance: 2,090 calories

- Extreme weight loss (~1.42% of body weight weekly): 1,090 calories (btw, “extreme” is not my phrasing; it was the calculator’s)

That’s a 1,000-calorie deficit.

You’d have to find a way to decrease your food intake, increase your physical activity, or, most likely, leverage a combination of the 2 to hit that. It’s going to be a real struggle.

So, if you want to go fast, don’t get over-enthusiastic.

Stay within the range of losing <1.4% of body weight weekly.

Nobody said losing weight fast is easy

Before we hastily conclude that fast (but not too fast) weight loss is comparable — or even sometimes more ideal than — slow weight loss, here’s a quick reality check.

Trying to lose weight fast is not a walk in the park.

You’ll have to be way stricter with your calorie intake and physical activity levels to see the results you want.

For some people, this can be a very unenjoyable and torturous process, which makes staying on track challenging.

A 2023 study highlights this perfectly well.

Researchers randomly assigned resistance-trained participants to 2 groups:

- Severe energy deficit (greater overall calorie deficit)

- Progressive energy deficit (smaller overall calorie deficit)

All participants followed the same exercise training plan and macronutrient split.

Here’s the surprising bit: after 8 weeks, there were no significant differences in body mass and fat mass loss between the 2 groups.

Why? Because, starting from week 3, adherence began to wane in participants assigned to the severe calorie restriction group.

Takeaway? There’s nothing wrong with fast weight loss. But achieving it in the first place is going to be very difficult.

Carefully consider the pros and cons

To take a more moderate stance and to sum up everything:

Fast or slow, what’s best for you depends on your priority, what you’re motivated by, and your ability to stick to a higher energy deficit.

No matter which path you take, though, always remember that successful weight loss doesn’t mark the end of your battle.

Remember the 2014 study mentioned back in the beginning? Around 76% of those who’d lost ≥ 12.5% of their body weight had regained it by the 3-year mark — regardless of whether they’d lost it fast or slow.

Have a plan to keep the weight off

A large body of evidence agrees that long-term weight loss is incredibly rare. (But not impossible.)

This means you must have a plan for preventing weight regain.

How? Diving into everything you could do to keep the weight off could easily be a whole other article, and it appears I’m already so many words in, so let’s keep it brief.

This 2019 systematic review reveals the top 5 behaviors that are most predictive of long-term weight loss success:

- High amounts of physical activity

- Improved diet quality

- Consistent routines

- Self-efficacy for weight management

- Consistent self-monitoring practices

Whew. Now, whenever you’re ready, let’s make weight loss a reality.

Here are a few additional resources you may find helpful for your journey.

Physical activity:

Diet: